Since our last journal went live, we traveled to India to meet Oshadi Collective and see our four-acre regenerative cotton farm in person. The trip was a soul-stirring experience, affirming our deep seated connection to the project.

Our intent in pursuing this farm-to-closet approach has always been to reconnect with nature. We wanted to touch the soil, feel connected to the land giving us the fruits of our labor, and honor the people who are tending to it.

What we realized on this journey was much more. This is not just a mission to transform the fashion industry, but a process of discovery and learning for each of us. It’s regenerative for the soil, but also for the people involved. We were humbled by the wonderful folks of Oshadi Collective, their stories, and the kindness they bestowed on us. It was a gathering of minds who each brought their spirit and knowledge to rekindling a love for fashion that came from the ground up.

A Collective Journey To Regenerative Cotton

After three days of travel we arrived at the derelict four-acre plot that’s being transformed into a regenerative cotton field. We were thrilled. The plants were thriving, as were the weeds. And it seemed as though Mother Nature was elated as well. As we approached the farm, the heavens opened and rain engulfed the fields, an area that had been parched for years. Tamil Nadu has been struggling with drought for the past three years, but there has been record rainfall this summer and fall.

In the distance, a line of farmers were plucking away at the weeds, which were growing rapidly thanks to the extra rain. There was one woman, in particular, dressed in a bright red sari. She was sprightly, plucking away at the overgrown grasses gingerly. Her husband worked alongside her, making headway on the field of weeds.

For the past fifty years, this dynamic duo, Eswari and Kuppusamy, who are now in their late 60s and early 70s, have been working as farmers, cultivating lands and harvesting crops for landowners. Though they harbored the knowledge of organic and regenerative farming, and were so intimately connected to the day-to-day needs of the farm, few people, if anyone, had consulted them on their expertise.

In India, a legacy of zamindars, or land-owners from British rule, has created challenges for today’s farmers. Though these men and women work on the farms, they do not own the property. Instead, they just collect wages from the landowners who tells them what to grow and how. As a result, there’s a class-based friction between the two: the landowners rarely interact with the farmers on a personal level or learn from their hands-on experience.

We, however, could not be more keen to share a cup of tea with them. Under the shade of a small overhang, sitting on a jute cot, we took shelter from the cloudbursts. We spoke about our mutual love for the Earth, their dreams for their children, and our shared hopes for a more harmonious lifestyle with nature. The farmers were intrigued by us, and we by them.

Meet Our Hosts:

Eswari, Kuppusamy, and their son Selvam: a farming family that encapsulates the beauty and the challenges of organic farming in south India. Both Eswari and Kuppusamy remember the days that they would farm without chemicals. “The food tasted better then,” Eswari said. “And people had fewer illnesses and medical issues.”

That, however, is no longer the case. Their farm is not far from construction projects. Land is being eaten up all around to develop into roads, houses, or factories. It’s a story that’s not escaping any part of the world, even this small corner in Tamil Nadu.

Yet Eswari is optimistic. She says, “The earth is responding to what we’re doing, to this way of farming. The earthworms are back, the dragonflies have returned. The earth seems happier.”

Notes From The Field

Regenerating The Earth

Since the farm had been fallow during the previous season, we needed to inject life into the soil and support it as it converts over to an organic field. The regenerative philosophy, which we subscribe to, celebrates self-sufficiency. That is, a farm has all it needs to take care of itself; those resources just have to be utilized wisely and with care.

The farm relies on what grows around the farm to feed itself. We want this to be an ecosystem that breathes life into itself. It’s not only cost-effective, but it’s also a method of farming that works with the rhythms of Mother Nature.

Much of what comes off the farm, such as the weeds being thrown here, are repurposed.

Weeding

As we pulled up to the farm, the plot was covered in weeds. Weeds, though seen as the bane of most gardeners and farmers, can be nutritious plants that were once eaten, or used to heal the body. With the added rain, we were grateful to see the knee-high weeds, which we walked through and identified.

In between the blanket of weeds, the cotton crop was thriving. With the help of nearby farmers, the field was cleared in two weeks, giving space to the cotton crop to grow. The challenge with some weeds, such as nutgrass that had grown abundantly on the farm, is that it can take away resources from the crop, prevent it from getting enough sunlight, and leave the cotton undernourished. But, let’s not forget, not all weeds are bad.

The cotton fields had three primary weeds on the farm: nutgrass, quack grass, and carrot grass (parthenium).

Nut grass: This has been given the nickname "the worst weed in the world." But it was prized in many communities for its medicinal properties, especially for digestive ailments such as dysentery, parasites, and bowel disorders. Nutgrass features prominently in Ayurveda, an ancient knowledge of alternative medicine on the Indian subcontinent. Even today, the tubers of nutgrass are used as a fragrance, added to soaps and insect repellent.

Quack grass: Also referred to as couchgrass, looks like crabgrass and can quickly eat up fertile soil or a well-manicured suburban lawn. But quack grass is a nutrient-dense plant whose roots were ground up and eaten previously as a starchy meal or used to make bread. Yes it does take up nutrients from the soil, but it also helps prevent soil erosion by binding the soil - this is particularly helpful if you have an influx of rains and don't want the soil to wash away.

Carrot grass, or parthenium: This is an aggressive weed that was reportedly introduced to India in the 1950s in grain imports from the US. But new research indicates it may have a few redeeming qualities: parthenium is being tested to remove heavy metals and dyes from the environment. It appears in homeopathy and allopathy for medicinal properties, and has shown to be an effective insecticide and pesticide in certain cases. So is it all bad news? No, though the weed does multiply quickly and can cause respiratory problems and skin rashes for farmers working in the fields, making it necessary to remove.

Drip Irrigation

Although the rains have graced the farm, the soil has been dry for years. So for this first season, the farmers put in drip irrigation to ensure the crop was successful (the funding for which came from Fibershed, a Bay Area-based organization that’s looking to build healthier farming ecosystems in cotton here in the US and now in India).

Our goal is to have this cotton rain-fed as much as possible. Thus, when the rains came through, we were grateful to not have to use the irrigation system. As the rains have continued, becoming some of the heaviest rainfall that the region has seen in twenty years, the farmers use the drip lines mostly to feed the soil with the vermiwash. The bulk of the farm is being rain-fed.

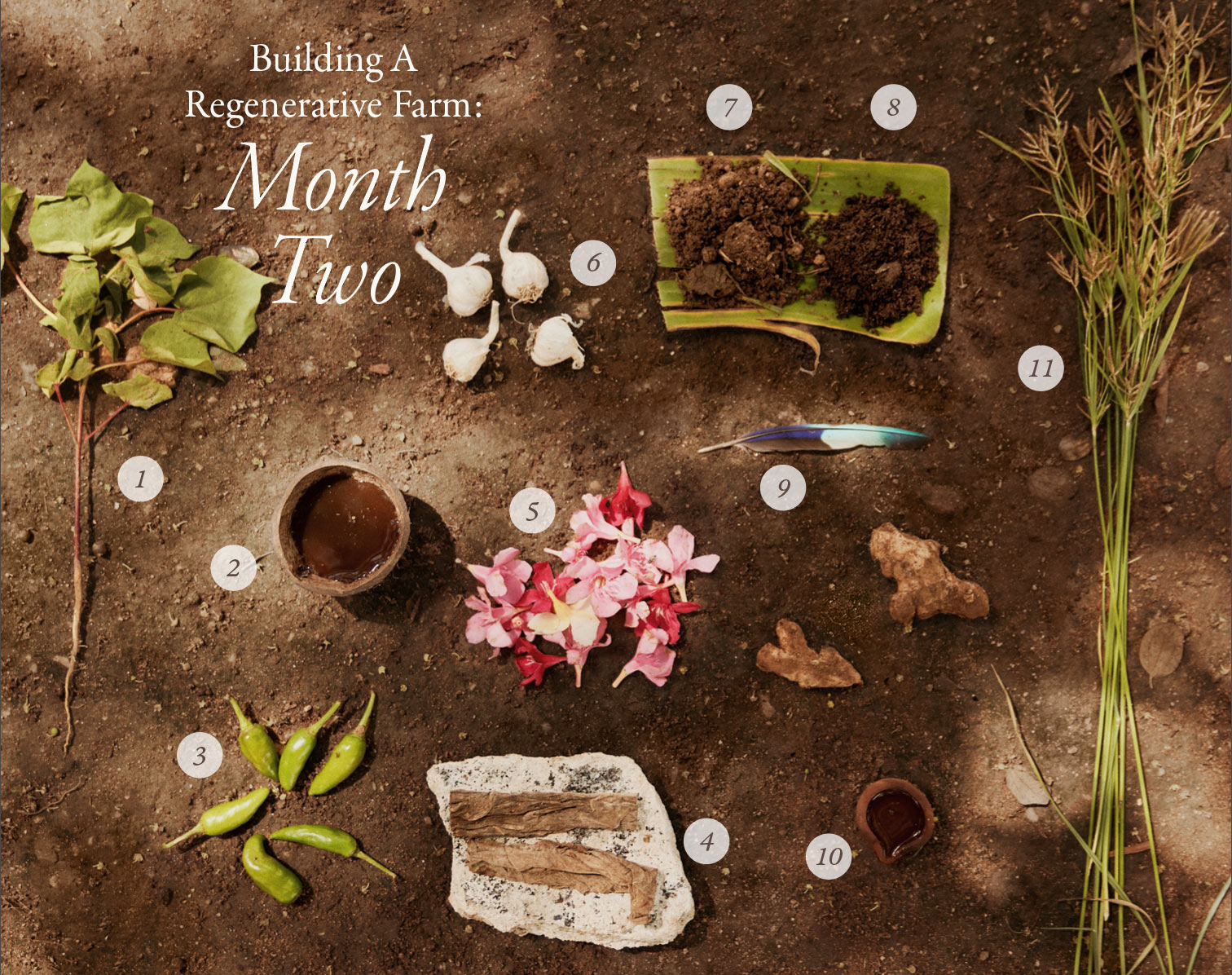

We’ve been using five methods to feed the soil and protect the cotton from pests at this stage of cultivation

What’s Next

Over the next couple months, we will continue to care for the soil and nourish the cotton. The farmers will plant cover, trap, and pollinator crops, as the cotton plants begin to flower. These small plants have so much potential and we are excited to watch them grow and transform into beautiful dresses.

Contributing Writers Aras Baskauskas, Christy Dawn Baskauskas, Esha Chhabra & Mairin Wilson